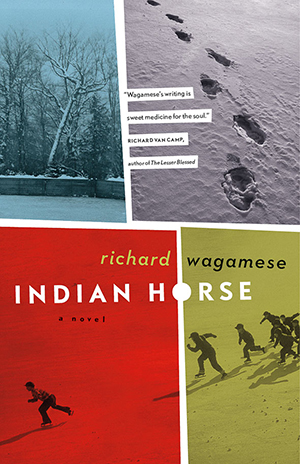

Indian Horse

by Richard Wagamese

Douglas & McIntyre

221 pages, $21.95

Reviewed by Candace Fertile

Richard Wagamese’s fifth novel, Indian Horse, is a must-read for Canadians as it marries two aspects of the country, one full of glory and one full of shame: hockey and the residential school system. Saul Indian Horse is a young boy when he is taken to one of the worst schools of a largely sorry lot, and he finds some salvation in the wonder of hockey.

Wagamese did not experience the brutality of a residential school, but his parents are survivors, and he has heard countless stories from others who endured horrific treatment, which everyone in the country needs to know about in order to have some small grasp of the challenges First Nations people face. Indian Horse offers readers the chance to see the harm caused by trying to erase another’s humanity, and this harm is not going to vanish quickly.

Saul’s early years are with his family in the bush of Northern Ontario, living a largely traditional Ojibway life. Naomi, Saul’s grandmother, is convinced that the family must hide the children from white people or they will be taken away. She’s right, of course, and the despair felt by Saul’s mother at the loss of children is heart-breaking. That Saul’s parents turn to alcohol is unsurprising. Their addiction further weakens the family even though Naomi tries her best to save Saul. Stories about his great-grandfather, who brought the first horse to Saul’s people, give him a sense of pride in his heritage, which is systematically destroyed when he ends up in the school. And Saul’s own story—the novel—may be his personal path to healing.

Wagamese excels at description. Saul’s narration of the harvesting of wild rice reveals his people’s connection to the land. It also reveals the split between his parents who have adopted Christianity and Naomi who maintains Ojibway beliefs. When cultures collide and one tries to crush the other, massive pain ensues. A belief system, such as Christianity, that celebrates suffering, tolerates and even encourages the infliction of suffering on others. The treatment of the children at the residential school is heart-breaking, and Saul shows how the degradation, both physical and emotional, affects the children and through them, whole cultures.

Relief for Saul comes through hockey, and the mysticism of Saul’s great-grandfather reveals itself in Saul as an extraordinary ability to see plays in hockey. The beauty of hockey motivates Saul to work hard, learning to skate, to pass, to shoot, and to move with an agility and grace that is the hallmark of the greatest hockey players. He does all this on his own after getting up early to clean the ice at the residential school. A kind young priest allows Saul to play hockey, and it’s clear that Saul has a gift.

Hockey becomes his salvation for a while. As Saul says, “We never gave a thought to being deprived as we travelled, to being shut out of the regular league system. We never gave a thought to being Indian. Different. We only thought of the game and the brotherhood that bound us together off the ice, in the van, on the plank floors of reservation houses, in the truck stop diners where if we’d won we had a little to splurge on a burger and soup before we hit the road again. Small joys. All of them tied together, entwined to form an experience we would not have traded for any other.”

Clearly having a community is central to happiness. When Saul moves away from his community, things change. On-going racism and the festering wounds caused by the crimes committed against him at the residential school take hold of him, and an excoriating anger results in alcoholism.

This novel had me on the verge of tears at several points, some full of sorrow and some full of joy. Throughout the novel, Richard Wagamese delivers an aching sensitivity and a wondrous hope.

Candace Fertile is a Victoria reviewer and a contributing editor to Coastal Spectator