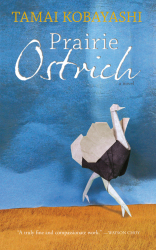

Prairie Ostrich

By Tamai Kobayashi

Goose Lane Editions

200 pages; $19.95

Reviewed by Chris Ho

The trials of finding one’s place in the world is something that everyone must go through (“yes, don’t remind me of high school,” you say), but Tamai Kobayashi’s distinct and cautious prose is woven with heart-wrenching elements of racial otherness, family fracture and religion. At times, Prairie Ostrich feels a bit like a diary of a young girl growing up, but what makes it unique is the way that Kobayashi intertwines and develops these themes while writing with powerful poetic voice.

Kobayashi’s debut novel is a heartbreaking story about the “only Japanese-Canadian family on the prairie” of Bittercreek, Alberta, in 1974. Kobayashi’s fictitious locale is a small town set in its ways and wholly non-accepting of diversity – whether it be religious or racial. Readers follow eight-year-old Egg Murakami through a grueling year in which she is bullied at school and feels isolated and neglected by her mother and father.

For Egg, stepping outside of her home often feels “like stumbling into a room where she does not belong, where Japanese turns into Jap.” Desperately and inquisitively, she searches for a sense of belonging, hiding away in the crevices of the school’s library to avoid the cruelest of bullies, Martin Fisken. While other kids might read fictional tales of talking animals and heroic kids, Egg finds comfort in the precision of the dictionary because “everything else [in life] is so muddled.”

After the mysterious death of her oldest brother Albert, her father exiles himself to the ostrich barn while her mother attempts to numb her pain through excessive drinking. Confused and alone, Egg somehow feels responsible for her family’s fractured spirit. Her sister, Kathy, tells her that stories help us make sense of life because they always having a purpose and a moral. But as Egg is surrounded by all the bad in the world, she can’t help but wonder: “What if there isn’t a Moral, or a Meaning? … What if God can’t do anything?”

Kobayashi seems to find a balance between the voice of an eight-year-old searching for meaning with the strong poetic language of the narrator – though at times I found it improbable that an eight-year-old would have the kind of intellectual depth that Egg expresses. This feeling took me out of the story from time to time: Egg is definitely not your average eight-year-old.

That being said, my only real criticism is that the dénouement seems rushed, and overly tidy. Throughout the novel, the narrator presents a few ways to look at adversity as Egg begins to realize that maybe there is no “moral to the story” in real life. But instead of transcending these viewpoints and concluding the novel with an enlightened and more complex moral message, Kobayashi opts for the predictable. I felt as though the “message” was that Egg turned out to be right in thinking that suffering is sometimes a blessing in disguise since it leads to personal growth. As for her other thoughts about life throughout the novel, well, she was just being naïve. Kobayashi rebels against that traditional feel-good ending; however she doesn’t take it far enough to avoid the clichés associated with those feel-good endings.

Chris Ho is a Victoria musician and freelance writer.

{ 0 comments… add one now }