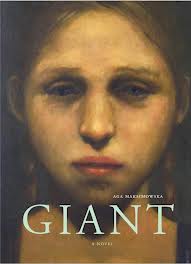

Giant

By Aga Maksimowska

Pedlar Press, 211 pages, $22

Reviewed by Judy LeBlanc

Reading Giant, Aga Maksimowska’s debut novel, I quickly found myself immersed in a world similar to the one inhabited by David Bezmozgis’ boy narrator in Natasha. Both books are infused with an Eastern European allure complete with culinary details, snippets of best-loved phrases in the native tongue, religious iconography and ritual, and a fraught political/ historical backdrop from which emerges the immigrant’s raw and courageous efforts to adapt to a new culture.

While Bezmozgis’s narrator is a Jewish Latvian male, Maksimowksa’s is an eleven-year old Polish girl named Gosia from a family divided by divorce. At age eleven, Gosia lives with her sister, her outspoken cognac-guzzling grandmother and communist grandfather in Gdansk, Poland during the 1980s while the solidarity movement simmers in the background. The sister’s teacher-mother (the only one in the family with a university degree) has emigrated to Canada two years before. Their hard-drinking father works on a container ship and appears sporadically bearing cheap gifts from Asia. The first half of the book chronicles life in Gdansk complete with pubescent angst and the usual firsts: bra, period, sexual encounter, all coloured by Gosia’s relationship with her grandmother and longing for her mother. If it weren’t for tragic-comic scenes like the one where a portrait of the pope and the black Madonna look down on a violent argument between the grandparents or another where a monstrous carp swims in the bathtub awaiting grandmother’s cleaver, I might feel trapped in an early teen book. Sometimes the voice – first person present – rings with an implausible maturity and language, generally plain and unsentimental, is peppered with too many flat, over-used expressions.

These problems are resolved in the second half of the book when I felt finally that I joined Gosia and her sister in their new life in Toronto with their strong-willed mother. Here, the story unfolds as the immigrant story does: the love/hate relationship with the adopted culture and its new language, menial work and the everlasting struggle to make ends meet, prejudice and ignorance. One of Gosia’s classmates carves a swastika into a bench where she sits. “It’s tiny but the grooves of its lines are deep.” Gosia’s loathing of her overlarge body, while emphasized to excess in the early part of the book is now symbolic of her general social awkwardness. Ultimately, it is the women in this story who triumph. Their strength is most evident in a memorable scene where Gosia and sister with mother and her Polish women friends celebrate the election of Walesa, heralding a new era of freedom. It is evident again when Grandmother urges Gosia’s mother to “stop waffling” and choose between Poland and Canada. On a personal level, the women in Giant, like Poland, choose freedom, complete with its confusions and pitfalls. These women have depth, gusto, and deep affection for one another, so much so that their presence lingered with me long after I had finished the book.

Judy LeBlanc is a fiction writer and a recent grad of UVIC’s MFA program.