Are You my Mother?: A Comic Drama

By Alison Bechdel

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

297 pp. $25.95

Reviewed by Chris Fox

Fans of Alison Bechdel will be interested in her second family-based graphic novel, Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama. The graphic skills that made Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For and Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic immensely satisfying and readable are on display in Bechdel’s latest offering. I was thrilled when Bechdel made the leap from comic strip to graphic novel with Fun, which I read voraciously and loved. So perhaps my expectations of Are You My Mother? were impossibly high. While Bechdel’s drawing retains its appeal in her third book, the narrative is less lively than that of Fun. Nor is the work as a whole as compelling as Sarah Leavitt’s Tangles: A Story About Alzheimer’s, My Mother and Me, the 2010 Canadian graphic novel that also tells the tale of a dyke and her mother.

While Fun was the story of Bechdel growing up in a funeral home and focused on her relationship with her closeted father, Mother? addresses the author’s more conflicted relationship with her female parent. The narrative line of Fun takes Bechdel through childhood and to university while Mother? explores primarily either the infant Bechdel or her adult self in therapeutic or romantic relationships. The most common settings of Mother? thus lack the graphic energy or interest that her more mobile childhood afforded. Far too many frames present Bechdel sitting with her therapist, a static situation that is not particularly graphic-novel friendly. Bechdel also recounts several dreams reminding me that, often, dreams are most fascinating to the dreamer (and possibly her therapist).

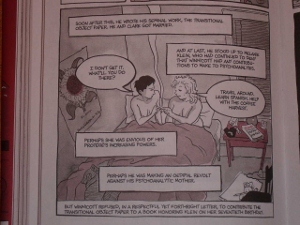

Ironically, I find Mother? leans too heavily in the direction of the academic essay. Although I have studied Jacques Lacan, it demands too much of the graphic memoir for Bechdel to present the theories of psychoanalysts Donald Winnicott, Alice Miller, and Lacan in such detail. Although I am in shocked awe at her boldness in titling a chapter, “Transitional Objects” and somewhat amused to see Lacan’s Écrits given graphic treatment, I found the many panels of text (complete with highlighting) excessive – and too static to enliven graphic narrative.

Nor does Bechdel quote psychoanalysts only. Virginia Woolf, one of my favourite authors, serves as her literary touchstone. Mother? includes textual panels from Moments of Being and To The Lighthouse. The Woolf references in Mother? parallel Bechdel’s use of James Joyce in Fun. It’s interesting, and slyly appropriate, that Bechdel uses the iconic father and mother of high modernism to anchor her relations to her own father and mother. Readers may also note a nod to gender in the colorful rose (or is it pink?), which gives many frames in Mother? the effect of retinted old photographs, and contrast with the verdigris of Fun.

Her use of quotation, which lacks the full integration of a really good academic essay, suggests Bechdel has not achieved quite enough distance on her therapy to integrate it fully into the literary graphic novel. The question in her title acknowledges that the story is about Bechdel’s search for a mother rather than about her mother and its present tense implies that that search is on-going, not yet resolved. Mother? might be read as Bechdel’s own Drama of the Gifted Child (the Miller book she quotes) – her sincerity and her gifts are indisputable. Certainly, readers who share similar issues may well forgive the dynamic limitations of Mother? and not only enjoy, but benefit from Bechdel’s psychoanalytic research and insights. For me, there isn’t enough graphic comic in this Comic Drama.

Chris Fox recently completed her PhD in English – which has not diminished her sense of humour